Some weeks ago, I read an excellent biography, Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, by one James S. Hirsch. Published in 2010, it relied on lengthy interviews with Mays himself and with people who had known him at many stages of his life. And it pointed me to an interesting illustration of race relations in the 1950s--a far more complicated story than many today would have us believe.

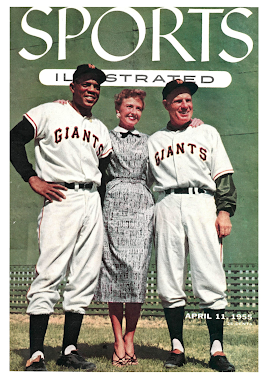

Willie Mays became a national celebrity in 1954, his second full year in the majors, when the New York Giants won the pennant and the World Series, highlighted by his extraordinary gave-saving catch in its first game. (Fans today will never see a catch like that, because we have no ball park in which a center fielder could run that far to make it.) In recognition of this, the new magazine Sports Illustrated--which had debuted during the 1954 season--featured Mays, his manager Leo Durocher, and Durocher's wife, the actress Laraine Day, on the cover of its April 11, 1955 issue. I am reproducing that cover below. Please look carefully at the right and left shoulders of Mays and Durocher, respectively.

Sirs:

. . . Up until now I have not found anything in particularly bad taste in SI, but by golly, when you print a picture on the cover (SI, April 11) in full color, of a white woman embracing a negro (with a small letter) man, you make it evident that even in a magazine supposedly devoted to healthful and innocent sports you have to engage in South-baiting.

I care nothing about those three people as individuals, but I care a heck of a lot about the proof the picture gives that SI is part of the giant plan to flaunt all decency, so long as the conquered of 1865 can be reminded of their eternal defeat. This is the kind of sporting instinct SI has! . . . F. M. Odom, Shreveport, La.

Sirs:

. . . To tell you that I was shocked at SI's cover would be putting it mildly. . . .The informative note inside the magazine tells me that this is Mrs. Leo Durocher, a white woman, with her arm affectionately around the neck of Willie Mays, a Negro ballplayer. . . .

Let me say to you, Sir, the most appalling blow ever struck at this country, the most disastrous thing that ever happened to the people of America, was the recent decision of the Supreme Court declaring segregation unconstitutional. . . . Edward F. Webb, Nashville, Tennessee

Sirs:

Please cancel my subscription to SI immediately. . . .This is an insult to every decent white woman everywhere. T. B. Kelso, Fort Worth, Texas

Sirs:

. . . .Such disgusting racial propaganda is not fit for people who are trying to build a stronger nation based on racial integrity. A. C. Dunn, New Orleans

Sirs:

In regard to your April 11 cover, it is the best yet. Albert L. Taborn, Cleveland.

[end letters]

Some of you may be wishing that SI had chosen not to print these letters--but I think that would have been a dreadful mistake. Had they done so, no one would have seen the letters that appeared in the following week, on May 2.

Sirs:

Believe me when I say that the three Southern gentlemen who spoke their piece on your April 11 cover are not typical of our attitude toward the colored race or our opinions on sports. The flavor of their thoughts is reminiscent of electioneering in Mississippi hamlets. You may have offended custom, such as it is, but you're right on the winning side again--this time the right one! Joe Attlees, Birmingham, Ala. [Willie Mays's home area, by the way.]

Sirs:

I am embarrassed beyond words and infuriated to the point of battle, concerning those letters from the good Americans in Tennessee, Louisiana and Texas who thought your cover was "racial propaganda" and "an insult to white women."

As background, allow me to state that I am a native North Carolinian. I lived for 21 years in the same South as these caustic readers, attended an all-white school, rode int he front of the buses, ate and went where I pleased. My ancestors fought on the same side in the Civil War as did theirs, and they got the same tar beat out of them just like all the rest. I, a true Southerner who have lived in New York less than two years, am still admiring what I think is one of the most democratic typcially sportsmanlike covers ever printed.

Willie Mays is an American baseball player first, last and always. He waves no flags, he stirs no trouble, his teammates like him, he has no axes to grind. he is the personification of liberty, initiative, democracy and fair play. Willie is a top-notch baseball player; his only discriminations are against opposing pitchers, his only philosophy is to play good, clean baseball. Norwood W. Pope, Jackson Heights, N.Y.

Sirs:

After reading the letters of Messrs. F. M. Odom, E. F. Webb, T. B. kelso and A. C. Dunn in THE 19TH HOLE (SI, April 25), I was shocked to see that such strong negative reactions to SI's April 11 cover should prevail in this great democratic country of ours. I would like to point out to the authors how warmly the essence of their letters would be received in Moscow, Russia.

I am quite sure that when SI printed the cover there was no intention of South-baiting, recollecting the Civil War, insulting any women or spreading racial propaganda on the part of the editors, as these gentlemen claimed. As a matter of fact, the sooner the authors of these letters and people with similar feelings realize that they are wrong the better off the United States will be in the eyes of the peoples of the world who we are tring to win over to our side in the battle against Communism. A.P.L. Knott Jr., New Haven.

Sirs:

I have never written to a magazine before, but I consider it my duty to do so at this time. I was disgusted at the letters concerning the cover of Willie Mays and Mrs. Leo Durocher. I may b only 15 years old but I have more common sense than any adult with those ideas. Steve Kraisler, Long Beach, N. Y.

Sirs:

Referring to the letters to the editor from Messrs. Odom, Webb, and Kelso and Dunn, concerning your cover of Willie Mays, Leo Durocher and Laraine Day.

To be putting it mildly, the aforementioned people are narrow-minded and absolutely poor sports on their criticism of that particular cover. I come from the South myself, and where I come from that sort of letter would be considered completely unfair. I doubt if any one of these people are more model citizens than Willie Mays and they'll have to come a long way to be as successful as he has been under the odds that he's had to face. I think that those people could do well to apologize if they are any kind of sports at all. Robert M. Young, Putnam, Conn.

Sirs:

I wish the postal regulations would permit me to address a few words to Messrs. Webb, odom and Kelson; however, the issue on which they saw fit to deliver their little verbal convulsions won't be an issue too much longer, and thus is nothing on which to waste my deathless prose. Betsy Wright, Muncie, Ind.

One week later the May 9 issue featured two more letters and an editorial note.

Sirs:

In keeping with the rest of the human race, I am often disturbed when someone says something that doesn't agree with my way of thinking. Too often I just quietly sit down and fume. It has happened when I've come across certain opinions expressed in the 19TH HOLE [the SI letters column.] It is rare indeed, however, that I become furious enough to writ a letter. But the time has come: I am now completely furious.

I see in your April 25 issue that four folks from our Southern states were shocked when they saw a picture of Mrs. Leo Durocher, a human being and a United States citizen, with her hand on the shoulder of Willie Mays, another human being and likewise a citizen of this democratic country.

Now I don't want to get into racial controversy with these folks. No doubt their ideas are, unfortunately, far too imbedded in their minds to be pried loose by me or anyone else. But I would like to say this: surely, if our own great world of sport is to be subjected to the tumult and the shouting of prejudiced fools, we have a truly fearful problem in trying to have the rest of the world play fair with us and with one another. I would like to know what other readers think on this issue. Doug McKay, Salt Lake City.

[Editorial note]: As we go to press, 178 citizens from parts of the country, including the South, have joined Mr. McKay in protest against the letters of Messrs. Odom, Webb, Dunn and Mrs. Kelso. Twenty-one readers followed the latter in objecting to SI's April 11 cover of Willie Mays and the Durochers. A Californian, protesting the original letters of condemnation, took a mock-serious stand on yet another cover:

Sirs:

To paraphrase the delightful emanations from the deep South that appeared in SI, April 25:

Up until now I have not found anything in particularly bad taste in your magazine, but, by dern, when you print the picture of a Sherpa tribesman on the cover of an American magazine (SI, April 25), it's shocking, positively shocking! Sir, the greatest blow ever struck at this country was the conquest of Everest by an indian (with a small letter) native villager. Your cover was an insult to decent white mountain climbers everywhere. It makes SI part of a monstrous conspiracy to undermine the mountaineering sport in this country. Sir, Examine your position! Rich Reid, San Fernando, Calif. [end letters.]

The racial issue in 1955 was just what it had been at least since the Revolutionary War in these United States, the subject of a great political battle, with millions of white and black people on both sides. The distribution of the letters to the editor give a reasonably good idea of the balance of opinion in the nation on the question of segregation and equal treatment at that time. I do not think that today's controversies on social media show us to be a more intelligent and enlightened citizenry, on the whole, than we were then. The letters show the same spirit that one can find today in the film 12 Angry Men or the broadcasts of Edward R. Murrow, such as Harvest of Shame, available on youtube. This was the country I grew up in, and it made me what I am. I am thankful for that.